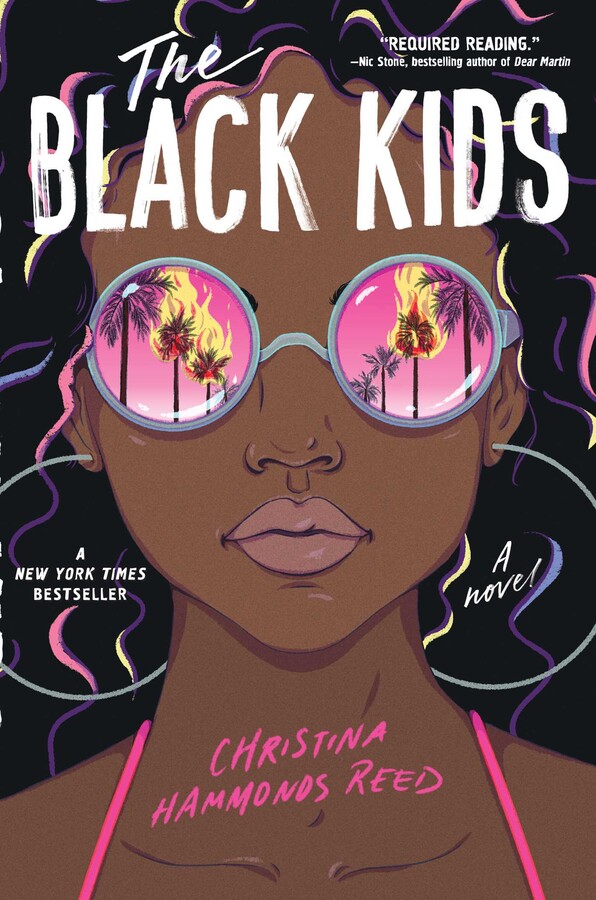

In Los Angeles in 1992, race relations are reaching a fever pitch. As riots roar through the city in response to the police beating of Rodney King, high school senior Ashley Bennet is facing her own reckoning. The school year is coming to an end, she feels as though she’s losing everyone she loves to other priorities, and a rumor she starts reaches a fever pitch of its own, at her wealthy, predominantly white, private high school. With significant parallels to our current times, Christina Hammonds Reed’s The Black Kids, out now, is about coming-of-age in a fire, both literal and figurative – little sparks of tragedy in a teenager’s life, as the world quite literally, burns around her.

Vanessa Chan: Where were you when you found out The Black Kids was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Christina Hammonds Reed: I was at my day job at the time, which incidentally was the day job I most enjoyed out of the many random jobs I’ve had over the years. My agent called me so I rushed out of the office to take a “coffee break”. When he shared the news with me, I could barely contain my excitement. I was jumping up and down in heels outside a very corporate building in Downtown Los Angeles. Then I calmly and rather anti-climactically went back to work. I didn’t really share it with people outside of my super close circle of friends. I was terrified it would all be taken away. Eventually, I had various celebratory dinners and drinks with my family and closest friends. But the day itself was especially meaningful to me because I received the news finalizing the deal on the one-year anniversary of my grandmother’s death, so there was so much joy to be had in a day that otherwise would’ve been painful.

VC: Which did you write first, the novel or your short story (published in One Teen Story, Issue #41)? And how long did the novel take you to write?

CHR: I wrote the short story first! I had the idea kicking around in my head as a graduate thesis film back in 2010, but ultimately decided against it. However, the story wouldn’t let me go, and just felt increasingly imperative with the rise of smartphones documenting police brutality and the effects of unequal policing on Black and Brown communities over the last decade. When the short story was published, I was un-agented. My (eventual) agent reached out to me and we had a really great meeting where he asked if I had considered expanding it into a novel. My first impulse was actually to say I’d said what I had to say, and was ready to move on to the next story. But the more I thought about it, it really did feel like there was so much left to explore, specifically as it relates to class, race, mental health and what it’s like to come of age as a Black girl with some degree of relative privilege. The novel took about two and half years to write from outline to submission. I had a job that entire time and was grieving the death of both of my maternal grandparents, so it took me a little longer than I’d hoped. But it also helped me stay focused on something other than grief. The task of completing it felt like a way of honoring them.

VC: In the novel, there is a point where a well-meaning friend tells Ashley that she’s not, “Blackity Black.” A lot of the story references the different ways where Ashley is either “too Black” or “not Black enough.” Why is this part of her identity important to interrogate?

CHR: I think for those of us who grew up in non-Black areas and going to non-Black schools, this is very much part of the microaggressions we were regularly subjected to because the media portrayals of Blackness, up until very recently, have been so limited. Film, music, books, visual art, all of these, seep into our consciousness as a society and when those images are focused solely on Black struggle and degradation, non-Black people will look at a Black person who doesn’t fit that stereotype and say, “Well you’re not that. Therefore, you’re not Black.” Which is absolutely incorrect. The Black community isn’t and never has been a monolith and while we have this powerful shared and unique experience of being Black in America, Blackness doesn’t only look like one thing and never has.

VC: It seems as though this novel is both an homage to and an indictment of the city of Los Angeles. What do you love and mourn for in LA?

CHR: I love the socioeconomic, cultural and religious diversity of this place. I love the geographic diversity of this city. I love that LA in its current iteration was actually founded by Black and Brown folks, as well as originally being the land of the Tongva people. And what I mourn is that these same people who helped make this city as beautiful and culturally rich as it is are being pushed out because of the economic realities of being unable to compete with wealthy transplants, rising housing costs, and a more stratified economy. Even homes in what was traditionally considered the hood up until fairly recently are now going for over a million dollars. Gentrification and revitalization projects are good for some but often they come at the expense of Black and Brown people who get pushed out of places they’ve called home for generations. And really that gentrification has been enabled by years of neglect, of political and economic disenfranchisement in the years leading up to and following the riots, from which many of these Black and Brown communities never fully recovered.

VC: You were eight years old when the LA riots broke out; your character Ashley is a senior in high school. What did it take to imagine her world at the time? What were your resources—your own memory, or conversations with family/friends, or historical research, or anything else? Did you draw from parallels in the present?

CHR: I was young at the time, but old enough to remember the fires, the anger and hurt of people who looked like me on the screen. I remember wondering why they were in pain and how it related to my personal experience of blackness. Similarly, Ashley is questioning herself and her community albeit in a much more mature way. That said, I still had to do a lot of research to make sure I was getting things right, even down to flipping through old issues of Seventeen and Vogue, etc. to see what Ashley and her friends would be wearing. Of particular help was Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 and a compendium of articles by the LA Times called Understanding the Riots, among others. I also spent hours on YouTube watching news reports, listening to music, and watching music videos of the era and the stories told therein. I wanted to fully immerse myself in 1992 and what it looked and sounded like. Also, one of the benefits of writing about somewhere where I currently live, is that everyone I spoke to about writing the book would offer memories of what their experiences of the riots had been. It was like we had shared this moment as a community and there was absolutely a desire to reminisce and reflect on it.

Honestly, I didn’t have to try too hard to draw parallels to the present. They’re inherent in this moment, unfortunately. Things have changed a bit, but also as we’ve seen with the recent George Floyd protests and the national and international outcry over the deaths of Black and Brown people at the hands of police, almost thirty years later we’re still grappling with how structural and systemic racism lead to a police force that doesn’t actually protect and serve all of us.

VC: You have a career and background in film and TV production. Did that aid you in writing this book?

CHR: Traditionally, screenwriting is very structured. There are very specific moments at which the inciting incident, rising action, climax, and denouements should theoretically take place in a conventional three-act structure. I relied on that in the outlining of the novel and making sure that I was moving plot along even within the more meandering context of Ashley’s interior shift. That said, I frequently blew up what I thought the plot was going to be along the way, most especially in the third “act” of the book. Mostly, I think it helped me not feel overwhelmed by what at the time felt like a very Herculean task. Especially given that it was my very first attempt at writing a book.

VC: What is the one thing you want your readers to take away when they read The Black Kids? What kind of advice would you give young Black writers?

CHR: I purposefully wrote Ashley as an incredibly flawed character because I thought it was important to illustrate that it’s not about where you start, it’s about where you end up. She makes huge mistakes over the course of the book. She hurts people and herself. She isn’t as informed as she should be. But she grows to be kinder, more empathetic; she takes ownership of her mistakes, and speaks up and out. She starts to love herself and really see herself as part of a larger community. I hope to convey to younger readers that it’s OK if you don’t have all the answers. Messing up is part of life and what’s important is personal growth. And I hope that it builds empathy, awareness and an even stronger desire to advocate for Black lives in non-Black readers who may not have inhabited a world like Ashley’s before.

To young Black writers, I would say, Your stories are important and worthy of being shared and you don’t need to seek validation from the “right” schools or the “right” programs before you can consider yourself a “real writer.” Also, be kind to yourself right now. This is a moment that can be especially stressful for one’s mental health given that not only are we in a pandemic, we’re also in a moment of huge racial reckoning in which the oppression of Black, Brown, and trans bodies is at the forefront of the national conversation. It’s OK to feel drained or depressed and less focused on writing as you normally would. Take care of yourself and eventually, when you feel stronger, use your writing to subvert, to inform, to speak truth to power, and to showcase our joy and our love.

This interview first appeared at One Story.

Vanessa Chan is a Malaysian writer who writes about identity, colonization, and women who don’t toe the line. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Electric Literature, Conjunctions, The Rumpus, Porter House Review, and more. Vanessa is a Fiction editor at TriQuarterly, and an MFA candidate at The New School. This follows a 10-year career in public relations, including most recently as director of communications for Facebook. Her writing has received support from Tin House, Mendocino Coast Writers’ Conference, Aspen Words, and Disquiet International, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. She can be reached at @vanjchan.