“Absconding is not the same as swarming. When a [bee] colony swarms, it splits in two parts: one part stays in the old home and one part finds a new home.” The swarm is a time when bees are at their most vulnerable. Without a home, they survive off the food they ingested before leaving the old hive.”1

The place I call home is built on the sand. You know it through sound—just before daybreak in the compound, a soft, rhythmic scrape begins. You will wonder what it could be; surely everyone is still asleep in the darkness. Then, you will realize that it is the sound of a straw broom meeting sand. Looking out of the window, you will see the silhouette of a figure bent over, crafting this peculiar song, sweeping the night away for the sun. As the sky changes from dark to light gray without ceremony, roosters add depth to the simple tune. Dawn is anything but quiet here.

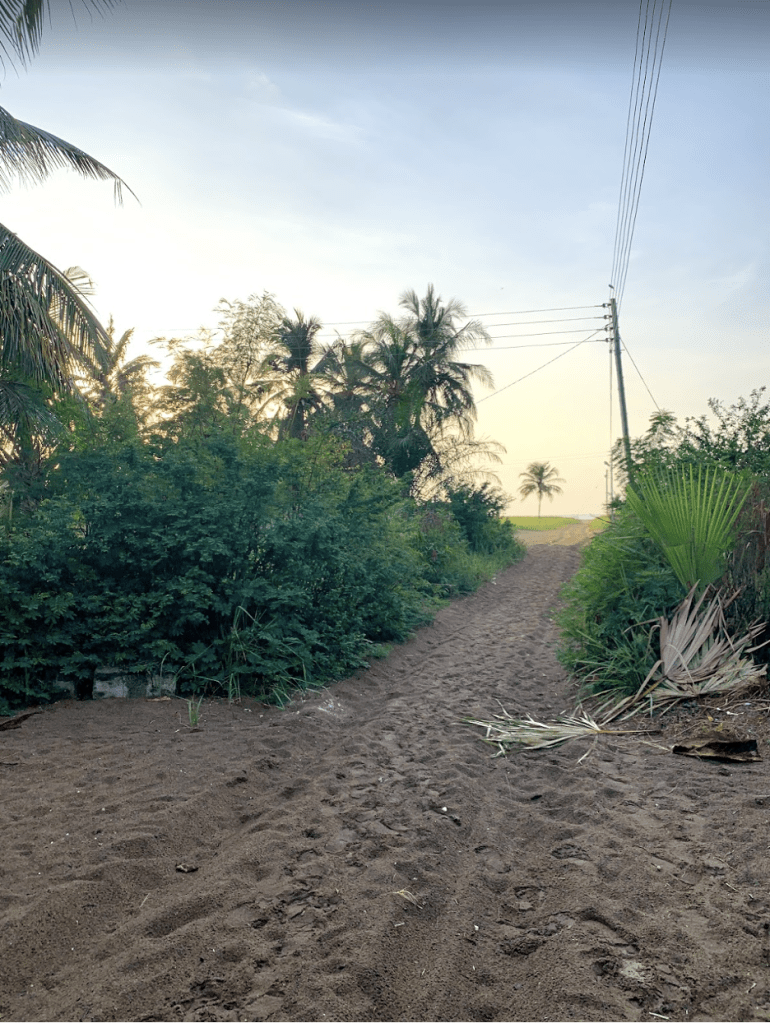

You will rise slowly, the ocean beckoning you. On the brief walk to shore, your bare feet will search for stable footing, pressing gently as the sand gives way. Eŋua ke, you will say to each person you pass, these words comprising the warm dew. The phrase states the evident—that the day has dawned. But it is spoken as a prayer of gratitude, a nod of understanding between us whose hearts still beat, whose souls and bodies are not yet separated. You will look each person you pass in the eye, greet them, acknowledge their being.

And then you will find the sun at the shore.

Our star pushes through the warm saltwater air, moving steadily across the sky. The scale tips as the planet turns and you slip from light to dark, as from dark to light. It is time to sleep once more.

In the Eʋe conception, the human soul is composed of three parts: (1) gbogbo, the life spirit (2) luʋo, the personality soul, and (3) ŋutila, the physical body. While the gbogbo embodies a person’s conscience, the luʋo constitutes the essence of a person. Dreaming is said to be a state in which the luʋo departs our physical body, drifting through the world of its own accord. Our essence leaves us for a time, unmoored without memory.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o writes of language as the bearer of culture and memory. It can be said then, that language is the essence, or luʋo, of a people. Held gently by the grammar of a language and protected fiercely but often invisible, is their worldview. Revealing whether time runs straight or turns in on itself, whether squirrels, soil, ponds, and the sea are imbued with the divine. In this way, language is not unimportant, but rather the bearer of all that we are.

Like many other immigrants, my parents left home hoping to live out the Dream. They left with eyes turned forward, hoping to make good on the promises of modernity and opportunity for their children. In this land of Dreams, my parents often spoke to my siblings and I in English as we were growing up, reserving Eʋegbe for conversations with each other. This has enabled us to understand but not speak the language fluently and unsurprisingly, this arrangement does not bode well for conversation. It allows for interactions marked by enthused nodding followed by periods of silence filled with broken sentences when our turn comes to speak. In this, we are not unlike many of my cousins in the diaspora—fragmented without the facility of the language of our heritage and adrift having inherited the Dream that characterizes these faraway places.

__________

My feet sashay in the warm sand as I sit low to the ground in Keta. I have returned home alone, beckoned by the memories that have made us who we are. Sitting across from my grandfather’s sister, I begin unsure of myself, my words feeling like they don’t fit in my mouth. She watches me as I stop and start, sigh and try to smile. But my language is not enough—not certain, not fluent, not enough. I want to ask about the woman I was named after—was she like me? Did she choose her words carefully? Love stories? Sit with her elders under the mango tree listening to words lifted by the wind?

‘Solastalgia’ is a word “used primarily to describe the negative psychological effect of chronic environmental destruction on an individual’s homeland, or the place they call home. The condition is often ‘exacerbated by a sense of powerlessness or lack of control over the unfolding change process.’”2

The sea began devouring the land in 1908, or thereabout. Since then, the water has danced, uncertain. Or perhaps stealthily with keen awareness, repeatedly shifting inland but retreating in the next breath to catch inhabitants unaware. The slow erosion of the place I call home has two origin stories. In one version of events, the erosion at Keta resulted because of confusion over financial responsibility for the sea defense, prolonging its eventual construction. In another version, the timing of the onset of the erosion reveals something else entirely. Coinciding with the appointment of Sri II as king of Anlo, who abandoned indigenous cultural practices in favor of European ideas about how one should be and what one should aspire to, the erosion suggests an ancestral intervention across realms. Emmanuel Akyeampong, a professor of African Studies, describes this causal relationship as an “ancestral critique of modernity.” After this, Home began to change.

__________

A long drive from Accra, those who have left Keta return most often because of death. Life, it seems, goes on elsewhere. At a funeral last year, I stood off to the side of a grave as a burial took place, watching as young women appeared and reappeared carrying water in large metal bowls. Young men mixed the water with the dry sand and shoveled the damp, brown mixture on top of my great uncle’s casket. The few relatives that had come huddled in groups, speaking quietly. Watching, as I was.

When a bee swarm occurs, what happens to those who go? Do they retain the memories of the place they came from? Etch the map in their eye, always knowing the way home? What does it mean to lose this map, then? To replace it with one that devalues our culture and way of being? Born and raised on the opposite shore, I know this place I call home mostly through spirit. And questions. What does it mean for home to disappear?’ The land but also the soul of a place? Is my fervent imagining a futile grasping at belonging, a wish for something that is not there, that soon enough might not be?

For us—children of diaspora, descendants of Dreamers—we were gifted precarity in the sandy shores and sturdy brick of our homes. How important then that we retain the memories that make us. From the places that hold our memory, our ways of existing in this world. How important then, that we wake up.

1. Rusty. “Why Do Honey Bees Abscond in the Fall?” Honey Bee Suite, 31 Jan. 2020.

2. Albrecht, Glen. “Solastalgia.” The Bureau of Linguistical Reality, 7 Apr. 2016.

This is the place:

This is where one hears the scrape:

This is me about to find the sun at the shore:

And this is the shore.

About the Author:

Fowota Mortoo writes essays that examine the intimately reciprocal nature of space and narrative. Deeply grounded in place and collective memory, her work explores themes of ecology, coloniality, and language.